Home > Stories and articles for spring > Bordeaux unclassified

10-MINUTE READ

A handful of Bordeaux châteaux dominate the headlines – but go beyond the classified growths and there’s a wealth of independent growers to discover. Charlie Geoghegan explains why these lesser-known properties are worth a closer look

Bordeaux is a place of contrasts: Left Bank and Right Bank, Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot, classified growths and “the rest”. But what exactly constitutes “the rest” is not always straightforward. “In the spring, the whole world comes to Bordeaux to taste En Primeur. But that’s only the great châteaux,” says Stéphane Derenoncourt, one of the world’s most respected consultant winemakers. “Then, in September, we have the Foire Aux Vins, the big wine sale at the supermarket. You have one spotlight on the very high quality, and another on the very low quality. In the middle, nobody cares. But for me, this is the heart and soul of Bordeaux.”

The classified growths garner most of the attention, but in reality, they represent a tiny minority of Bordeaux overall. There are around 110,000 hectares under vine in Bordeaux; the classified growths account for just five percent. The rest – the vast majority – operate outside the classifications. “They’re the same as the Burgundians or growers in the Rhône Valley,” says Max Lalondrelle, Managing Director of Fine Wine at Berry Bros. & Rudd. “These are just humble people trying to make a living.”

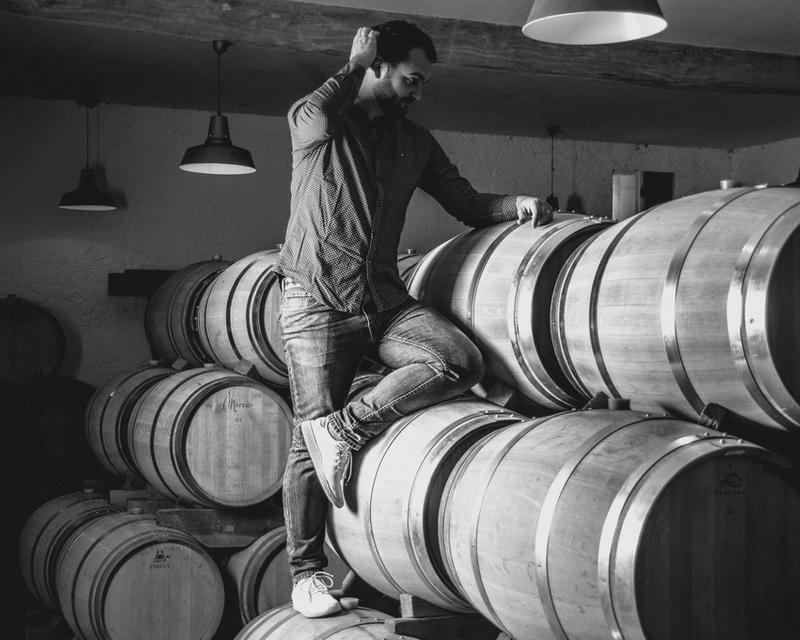

Wine consultant Stéphane Derenoncourt and wife Christine pictured at their property Domaine de l'A in Castillon-Côtes

Bordeaux’s unsung winemakers

It’s often said that Bordeaux is all business, particularly when compared to the artisans and paysans of Burgundy. But the idea that the Bordelais are all corporate, faceless traders doesn’t hold up to scrutiny.

Stéphane’s clients include classified growths on both banks of Bordeaux’s Gironde estuary. He understands their world as well as anybody. But his knowledge of the region runs a lot deeper: he consults for clients in many less lofty appellations, including generic Bordeaux. Crucially, he’s also the proprietor of Domaine de l’A in Castillon-Côtes de Bordeaux. He established both the estate and his consulting firm in 1999. “For me, it was impossible to consult without producing my own wine,” he says. “It’s my laboratory. If you want to help people to make wine, you have to make your own.”

One of those people that Stéphane helps is Antoine Darquey, the fourth generation of his family to run Ch. Teyssier in Montagne-St Emilion. In 1993, Antoine was working as a négociant (wine merchant) in Bordeaux; meanwhile, his mother had become concerned about the family property. She asked Antoine to take an informed look at it. “She asked me to see if things were as bad as she thought – or worse,” Antoine recalls. Her fears were not unfounded: “It was much more serious than she could have thought. The estate was totally in the red, in a very dangerous position.” Making the most of his relationships in the industry – particularly with the consultant Michel Rolland – Antoine took to rebuilding the property entirely. “Of course, it’s not a factory,” he says. “It wasn’t just about investment or rebuilding the facilities, it was about the terroir and the vines. These things take time.”

A short drive west and still in the Montagne appellation, Jeff Berrouet lives and makes wine at Vieux Ch. Saint André. The 12-hectare property, which has been in his family since 1978, is dubbed “a true insider’s wine” by Jane Anson in Inside Bordeaux. But if the family estate flies a little under the radar, the family name rings out loud and clear. A Berrouet has been the winemaker at Petrus since 1964; Jeff’s brother, Olivier, succeeded their father, Jean-Claude, there in 2008. Petrus – as with all the wines of Pomerol – is also unclassified, so Vieux Ch. Saint André is in good company. “My father has had a big influence on my philosophy,” says Jeff. “He likes to make a wine which can tell the story of its soil and its year. That’s important for us.” Though Jeff uses modern techniques and equipment, he has learned from one of the best in Bordeaux and seems quite content to carry on the family tradition.

Jeff Berrouet makes a true "insider's wine" at Vieux Ch. Saint André

David and Goliath

If this snapshot of individuals tells some of the story, it’s worthwhile to zoom out a little and take in the wider picture. There are around 5,660 producers in Bordeaux, a number that has been decreasing for some time. A key shift here in recent decades is towards vineyard consolidation, particularly when it comes to top communal appellations. “In the Médoc, the big châteaux have the power to snaffle any interesting parcels,” says Mark Pardoe MW, Wine Director at Berry Bros. & Rudd. “If there’s anything good, they’re going to buy it. So that pushes up the price of land.”

The 1855 classification allows châteaux to absorb new purchases – classified or not – into their holdings, provided that the land is within the same appellation. There’s a clear commercial incentive for deep-pocketed châteaux to buy out smaller growers. “Let’s say you are a top classified growth in Pauillac, and you buy land from your neighbour who sells their wine for €15 a bottle,” explains Max. “Technically, you could now sell that wine for €100 – or more – overnight. Even if the land is very expensive, it makes commercial sense.”

While this is all well and good for large players with financial muscle, the dynamic doesn’t work the other way. No €15-per-bottle producer is in a position to buy out Lafite, Mouton or Margaux. “There is a war in these regions to acquire land,” Max continues. “It’s fine for the properties that can afford it, but it comes at the demise of the smaller properties.” Establishing a small, independent operation in the Haut-Médoc communes – or withstanding the pressure to sell up – is hard work.

Detail of vines being pruned in Bordeaux. Photograph by Jason Lowe.

The efforts of a notable few are admirable. “There are a couple of boutique producers on the Left Bank,” says Mark. “Osama Uchida is one of them, doing exciting things on a very small scale based on what they can get their hands on.” The tiny Domaine Uchida was established in 2015, with under a hectare of biodynamic vines in the commune of Cissac in the Haut-Médoc appellation, just beyond some of Pauillac’s top terroir.

In Pauillac itself, the local co-op – known for its La Rose Pauillac brand – is still alive and kicking. “They’re one of the last bastions,” says Max. “They are untouched, but if it wasn’t a co-op it just wouldn’t work. And you can’t help but think that individual growers will eventually sell up, whether that’s this generation or further down the line.” Communal appellations Listrac and Moulis contain no classified growths, though there are a host of interesting producers.

The appeal of the Right Bank

For independent growers, the situation is perhaps more promising on the Right Bank. “There’s much more land there,” says Mark. “It’s expensive, but not so prohibitively expensive as the Left Bank. And there’s always been more of a sense of creativity here. This was the birthplace of the garagiste movement, which was iconoclastic in what it was trying to do.” The upstart garagistes produced low-yielding, high-octane wines from small, basic facilities, including actual garages. High critics’ scores and even higher prices caught international attention in the 1990s.

Some of the movement’s key proponents have become firmly established at Bordeaux’s mainstream high end: both Ch. Valandraud and La Mondotte are among the top classified growths in St Emilion today. The movement was relatively short-lived, but its influence lives on.

“So, there’s the availability of land, a culture of innovation and estates of a sufficient size to make production worthwhile. All these things come together to make the Right Bank a more interesting place for producers to consider,” Mark explains. Those appellations that lie just beyond the boundaries of St Emilion and Pomerol offer plenty of opportunity for ambitious producers who may otherwise be squeezed out. “The great châteaux are on great terroir. But outside the great names and regions, there are little pockets of terroir that have a lot of the characteristics that do genuinely define the great names.”

“My dream was to buy a first growth property in St Emilion,” recalls Stéphane, “but the bankers did not agree.” Instead, he and his wife, Christine, looked further east, to the hills of Castillon. They founded Domaine de l’A there in 1999, starting with a four hectare block. “This [St Colombe] is the first village past the boundary with St Emilion. There’s beautiful soil here. We are on the continuity of the southern hill of St Emilion, with the same sunny exposition.”

In the 1960s, Jean-Claude Berrouet managed some of Pomerol’s top properties on behalf of Jean-Pierre Moeuix: Petrus, La Fleur-Pétrus and Trotanoy, among others. In his capacity as a négociant, he also bought and sold wine in bulk from throughout the wider region; few individuals in Bordeaux would have been as knowledgeable or as well connected. It’s interesting, then, that he chose to set up his family estate not in Pomerol or St Emilion, but in the satellite appellation of Montagne. “It’s a good compromise here,” says his son Jeff. “We have really good terroir, and the land isn’t as crazily expensive as in St Emilion.”

Winemaking without constraints

Operating outside of the classifications and being small-scale – whether in hectarage or approach – has its benefits. As both a consultant to many classified growths and the proprietor of his own small domaine, Stéphane has a unique view. “As a consultant, you don’t necessarily have a lot of freedom. You have to respect the client’s history, the family, the soil and the technical side. You can change things a little bit, but you have some limits. With Domaine de l’A, my goal was to have total freedom: an estate without limits, where I could produce whatever I want.” And he does just that: “I don’t really like the white wine from Bordeaux,” he admits, “so I decided to plant some Chardonnay. I don’t care about the appellation, so it’s a Vin de France – but I can make the wine of my dreams.”

The reputation of the grand vin at Domaine de l’A exceeds its appellation. “My target was not to make the best wine of Castillon,” Stéphane continues. “I don’t care about that. Today on the front label, you see ‘Domaine de l’A’, the vintage and ‘Derenoncourt’. On the back label, you see ‘Castillon’ in very small writing. I wanted something at the quality level of the classified growths of Saint Emilion, yet still a good bargain for wine lovers.”

Since the beginning of Stéphane’s career, “viticulture” and “biodynamic viticulture” have been intrinsically linked. “My first job in Bordeaux was in Fronsac, working with Paul Barre,” he recalls. “He was one of the first growers working biodynamically at the time. I worked there for five years and then left for Ch. Pavie Macquin in St Emilion, where the viticulture was also biodynamic. So, for the first 10 years of my career, all I knew was biodynamics; I didn’t know there was something else. For me, it was very natural.”

Until recently, Stéphane was happy to quietly practice organic and biodynamic viticulture without any certification. Following pressure from customers, he decided in 2017 to seek organic certification; Domaine de l’A will be certified organic from the 2020 vintage. Both Vieux Ch. Saint André and Ch. Teyssier are working towards the highest level of France’s Haute Valeur Environnementale (HVE) certification, which promotes environmentally friendly viticulture.

Many producers have returned to a more traditional. low-intervention way of winemaking; here, horses are used in the vineyard

Challenges and opportunities

It’s a sad truth that few of the benefits of being small in Bordeaux are commercial in nature. One’s location on either side of a communal boundary can have a real impact on the bottom line. Antoine argues that his terroir at Ch. Teyssier in Montagne is the equal of – if not superior to – many St Emilion sites. But he sells his wine at a considerable discount versus his neighbours whose wines bear the St Emilion Grand Cru AOC label. “The only difference between us and them is that we sell our wine for less. Everything we do, we have Euros in our heads. It’s more complicated to balance the books.”

Getting these wines onto shop shelves is not as easy as it may appear. The Place de Bordeaux is the network of courtiers (brokers) and négociants that buy and sell Bordeaux wines for distribution around the world. It is not, it would appear, especially well suited to promoting fledgling producers. “Most négociants focus on the classified growths,” says Max. “It takes the same amount of time and effort to sell a €6 wine as a €150 wine. So, you may as well sell the more expensive one – and that’s to the detriment of many fantastic small producers. There’s nothing that would make me happier than to sell more of those wines. Whatever we can do as a business to encourage and support these properties is important.”

Given the challenges facing small producers, it is refreshing to see how motivated they can be. “People work hard here in Bordeaux,” says Antoine. “We have been accused in the past of being arrogant – and perhaps rightly so. If I only worked for money, I’d rather just stay at the office in Bordeaux. But it’s a question of passion, really. I’d be better off financially just selling classified growths. In the end, it’s passion – and also ego. You want to go further, to show that your terroir is great. My main reward is when we taste blind with friends, and when Teyssier performs as well as classified growths.”

A lack of classification may be a challenge for producers, but it represents a real opportunity for consumers. “Bordeaux today is so different to the Bordeaux I first came to 25 or 30 years ago. With a relatively small amount of money, you can get great wines these days,” says Max. “The techniques and costs of production are roughly the same between Montagne and St Emilion, but St Emilion is by default more expensive. If you buy your wine from somebody on the ‘wrong’ side of the appellation, you’re getting a bargain. Very often, these wines are comparable to classified growths, at a fraction of the price.”

Hidden-gem claret

Our Wine Director, Mark Pardoe MW, picks out three favourites from our range of lesser-known Bordeaux estates

2016 Ch. Teyssier, Montagne-St Emilion

This has a ripe bouquet, plump with red fruits; it’s both sophisticated and glossy. The palate is nicely composed, with an obvious floral fragrance. In the mouth, the wine is fresh, modern and appealing. The vintage adds a pinch of tannin, though in a supportive rather than intrusive way. This is very accessible – almost a crowd-pleaser – yet is also layered.

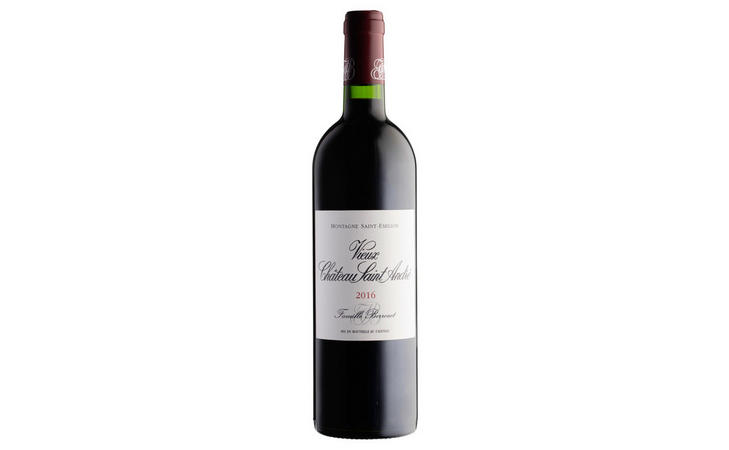

2016 Vieux Ch. Saint André, Montagne-St Emilion

The colour is remarkably intense and vivid at five years old. The bouquet is elegant and lifted, with a subtle hint of spice. The first taste is delicate and rather beautiful, held in check by the tannins, which also deliver a freshness and vivacity. There are thyme and liquorice notes. This is a wine of real interest: elegant and complex.

2016 Domaine de l’A, Castillon-Côtes de Bordeaux

Beautifully strung together, the 2016 Domaine de l’A captures the essence of Merlot and Cabernet Franc. A scented nose of black rose petals greets you amidst aromas of hedgerow fruit and black cherries. The palate is seamlessly balanced with very fine ripe tannins and a glorious velvety texture. The wine has a fine backbone and structure which gradually builds towards the back of the palate.