Home > Editorial > Curating our heritage

Curating our heritage

A look inside our archives

FIVE-MINUTE READ

From leatherbound ledgers to historical price lists, three centuries of trading have gifted us with an immense collection of documents. The unique task of curating this rich heritage belongs to Clare Rodger, eighth-generation member of the Berry family, and archivist Jon Newman. Alexandra Gray de Walden takes a closer look inside our archives

Of letters and ledgers

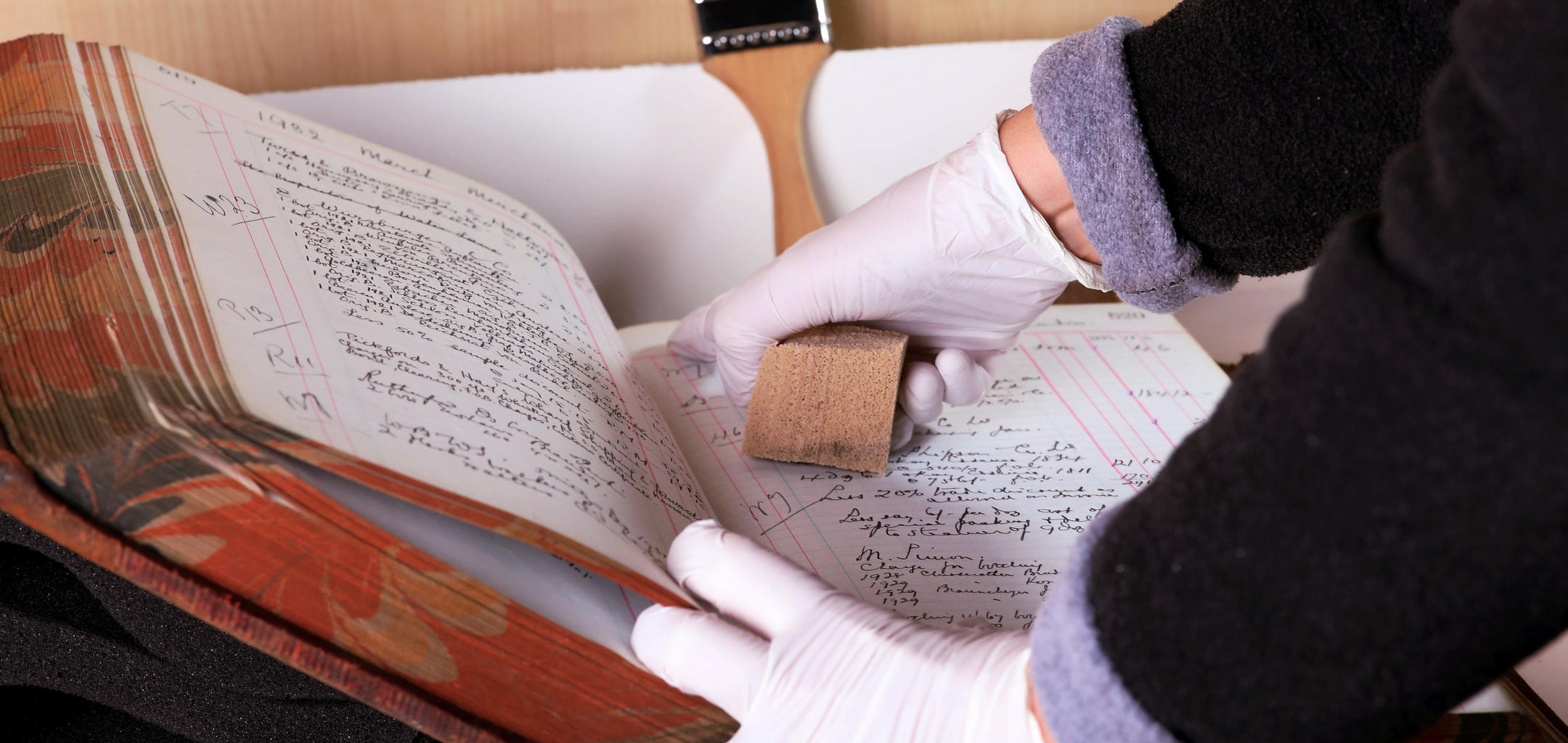

Spanning over 300 years of trading, Berry Bros. & Rudd has a gargantuan collection of archives – including sales ledgers, customer letters, historical price lists and our famous weight books. The great responsibility of curating our history falls upon Berry family descendant Clare Rodger and Jon Newman, who began working with us in 2018 as a consultant archivist. Together, it’s their task to record, in some cases repair, and ultimately preserve this collection for future generations.

A large part of our archives comes from our customer records. It’s impossible to imagine the exact number of individuals who have crossed the threshold at No.3 St James’s Street and bought goods from us. Many of these characters have come to form a part of our archives themselves, forever ensconced in history.

Our most well-known, and colourful, customer records are our weight books: entries of customers weighed on our historic scales at No.3.

“There are families who have been buying from us for a long time – they can find their ancestors’ weights in the weight books,” Clare explains to me. “Equally, there are producers we have worked with for a long time who are also in our ledgers. That is always very important for us: that we still value our customers and our producers. We would have no business without them.”

Delving into customers’ letters has also thrown up some interesting discoveries; Jon recently discovered a letter from the ill-fated Arctic explorer Gino Watkins. “He approached Berry Bros. & Rudd in the early 1930s, trying to blag some cases of Champagne for his expedition to Greenland,” he tells me. “Sadly, a few weeks later his empty kayak was found off the Greenland coast. I like to think that the company did supply him with the Champagne.”

“It’s impossible to imagine the exact number of individuals who have crossed the threshold at No.3 St James’s Street and bought goods from us. Many of these characters have come to form a part of our archives themselves, forever ensconced in history”

Resilience and reflection

While possibly considered some of the “drier” parts of the selection, our sales ledgers demonstrate the archival wax and wane in popularity of certain wines and regions. Prior to the First World War, our price lists were dominated by German wines, mostly from the “Moselle” as it was then referred to (now “Mosel”), outpricing Burgundy and some Champagnes. No prizes for guessing when and why this changed.

“The war years are very interesting to read,” Clare tells me. “You really understand how hard it was to maintain a business, how small ours was and how it has grown. We’ve had our recent challenges too: Covid, Brexit. These put real strains on the business, but it has coped with them.”

Having survived wars, disease and political disorder, Berry Bros. & Rudd’s reputation as the authority on fine wines and spirits is by no means a new one. As early as the late 1800s, the company was a key importer of Tokaji wine from Hungary, doing a great deal to popularise its consumption in the UK. Numerous samples of our early advertising extol its merits and list superlative vintages to collect.

“These earlier wine lists tell us about the limited range of wines that the company was selling then, compared with today’s much more diverse palate. And the relevant prices,” Jon explains. The opportunity to purchase 12 bottles of Volnay for 60 shillings in 1896 is, sadly, not something which has endured.

“You would not look back and say that it was the same business as it is today, because it is just not,” Jon continues. “We are a much bigger and much more commercial enterprise these days.”

Resilience, courage in adversity, historical insight; what else can be learnt from these myriad archives? “It’s easy to look back at successes, but it's equally important to look back at the not-so-good decisions,” says Clare. “Have we tried this before? Where did it go wrong?” Indeed, this past reflection and analysis may be the key to our longevity.

“Working with the archives, I have become very close to what has come before us. You are just a guardian – a very tiny cog in this very long history”

Preserved for posterity

Being part of an illustrious family-owned business is one thing, let alone being the guardian of its comprehensive historical archives.

“It is quite a responsibility,” Clare says. “Working with the archives, I have become very close to what has come before us. To see the family names, the people involved and what they did, you feel much more of a bond. You are just a guardian – a very tiny cog in this (hopefully) very long history. I feel a duty to pass it on in a better state than it was when I started here.” As the tempo of life quickens apace and more of our world moves online, it would be easy to dismiss the reams of leather-bound books and written correspondence as nostalgic ephemera, soon becoming obsolete and lost. Thankfully, Clare has other plans for conserving and sharing these historic snapshots.

“It is so important to preserve this physical history – we have probably only just got there in time. A lot of work must be done on repairing some books and ledgers so we can photograph them, put them online and ensure they are preserved for future generations. I hope digitising the archives brings it to life for people. Until now, many thought it something of a family indulgence, but it is very much key to our business.”

Both Clare and Jon hold the view that “it’s best to record and preserve archives as you go along” because “archives don’t stop” – just as history doesn’t stop unfolding. Today, the weight books and customer letters have outlived their respective subjects and authors. Who knows which of the living archives currently being recorded will be of most historical interest in another 300 years?