Home > Editorial > Fighting frost

SEVEN-MINUTE READ

Fighting frost

Spring frost, once a rare occurrence, is hitting vineyards ever more frequently, and with ever greater damage. Barbara Drew MW explains this threat and how vignerons can manage it.

Sharp spring frosts have been increasing in frequency in recent years. Even a decade ago, these were rare occurrences. But now, each April (and often even later, into the start of May), we see widespread frost damage in European vineyard areas – and not just those in the north. Vineyards all down the Rhône were hit in 2021. Just as with wildfires in California or Australia, what was previously a once-in-a-lifetime severe weather event has become depressingly commonplace, an annual tick on the calendar marking how much weather patterns are changing.

SPRING FROSTS

Frosts occur when air temperatures at ground level dip below zero degrees Celsius. Whilst this can happen throughout winter, when the vine is dormant, the risk of damage is very small. In fact temperatures have to drop lower than -15oC to cause serious damage in winter.

Spring, however, is another matter. At budbreak, tiny buds, followed by delicate leaves and shoots, start to appear on the vine. If temperatures dip below freezing after this point, and stay there for any length of time, the water in the capillaries will freeze, causing huge damage to the tender new growth.

In the Northern Hemisphere, the frost risk was historically well past by April. However, this pattern has seen serious disruption over the past decade. With a changing climate, vines are hitting budbreak earlier, due to warmer weather early in spring. Temperatures then drop – often dramatically – in late spring, with often devastating effect.

Frost damage can be magnified by bright sunlight. After a freezing night resulting in vines and buds being hit by frost, a cold but sunny morning has an effect similar to a magnifying glass on dry turf. The ice focuses the sun’s rays, causing a burning effect on the buds and shoots. This can devastate the parts of the vine responsible for the coming year’s growth. Worse, it can also cause sufficient damage that next year’s crop may be reduced as well.

Even without this burning effect, most spring frosts will either damage the buds so much that very little fruit is produced, or destroy the buds completely. If vignerons are lucky, secondary buds may appear after the frost to replace those that have been damaged – but these will be fewer in number, and given how late they appear, often there is just not time for them to ripen before autumn sets in.

PROTECTING THE VINES

Over the years, grape-growers have experimented with a number of techniques to help protect their vines. None of the techniques are foolproof, and many are seriously energy intensive - and expensive to boot. Nevertheless, choosing to do nothing to protect one’s vines against frost runs the risk of losing an entire year’s harvest, something most growers can ill afford.

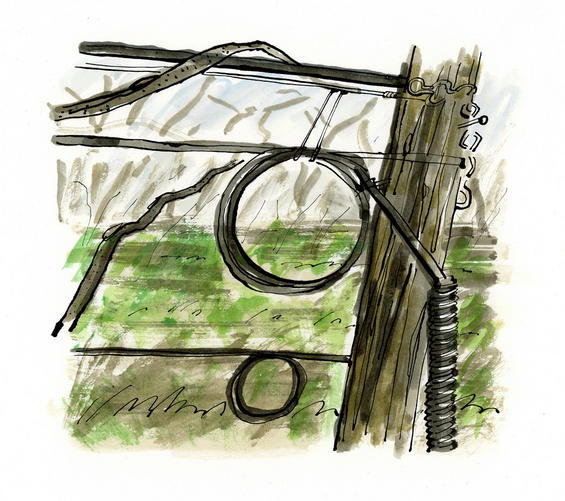

Candles

Sometimes called bougies or smudge-pots, these aren’t your typical household candles; they look more like tins of paint. Growers place them in the rows between vines, at greater or smaller intervals depending on how severe the frost is expected to be. The “candles” are filled with a flammable substance that raises the local temperature slightly, usually by a few degrees.

In some vineyard regions, an even more rustic approach is taken, with vine cuttings or any dry vegetation being used as fuel for the candles. In extreme cases, entire hay bales can be burnt in the vineyards, in an effort to heat up the air around the vines, and generate a warm blanket for the plants.

Understandably, this approach raises concerns around air pollution, especially as the smoke created from such fires does not remain within the confines of one vineyard. Solutions against frost are, by necessity, normally local, yet their knock-on effects can be widespread.

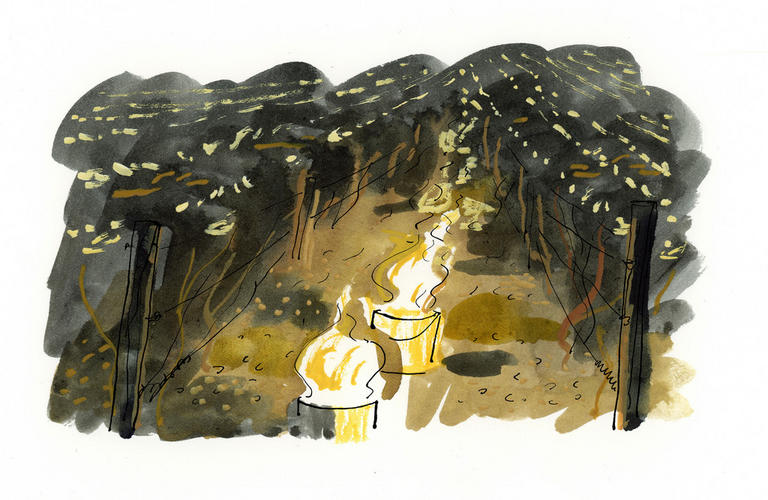

Wind turbines

Either mobile or as a permanent fixture in vineyards, wind turbines are used to circulate the air in the vineyard to prevent frost pockets from developing on the ground. Jean-Pierre Guyon believes that strategically placed wind turbines along the Côte d’Or could seriously mitigate the region’s frost problem.

However, such structures are not cheap to install, and affect the aesthetics of a region. This may seem like a small price to pay for frost protection. But some regions rely on tourism for income as much as their wines, so it is a consideration. How the wind turbines are fuelled is another aspect to consider. There is a risk that, particularly in rural regions, mains electricity may be insufficient to supply all the turbines in a vineyard area.

Helicopters

A more extreme version of this is using a helicopter to fly over the vines to circulate the air below. For obvious reasons, this is not an option available to many, and is one that comes at a considerable cost. Only the most deep-pocketed vignerons have this weapon at their disposal. Even where growers can pool resources, they are dependent on a helicopter being available for the nights they need, and being close enough to an airstrip for this to be a feasible option.

Aspersion

Using a sprinkler system, the vines are sprayed with water, which freezes over the delicate buds. This provides protection and insulation – keeping the buds at a constant temperature of just below freezing – rather than them suffering down to -6oC or lower, a temperature at which damage can be catastrophic. However, for this method to be effective, a few things are needed, not least a sprinkler set-up. In many European vineyards, where irrigation is not permitted for mature vines, sprinkler systems can be seen as an unnecessary investment.

For this system to be effective, the buds need to be completely covered in ice throughout the cold snap – which sometimes extends for three, four or more nights. As the ice will melt during the day, this means constant spraying is required during the evenings, which uses a huge amount of water.

For wineries looking to be as sustainable as possible, only using natural water sources on their own property, this can be enormously problematic. Often, they will only have sufficient water for one or two nights of spraying, leaving the vines unprotected if the cold snap persists for longer. There is also an added complication once the frost passes; the large volumes of melting water can drastically increase the risk of mildew in the vineyard too.

Heating cables

Powered by electricity from a generator or the electrical grid, these cables are permanently attached to the vine trellis and can be switched on as necessary. Whilst tricky to retrofit to a vineyard, they are easy to use if built into a trellis when a vineyard is being planted.

Requiring only a small electric current, these cables provide heating for a seven-centimetre radius around the nascent buds. Several vignerons in Chablis’ best vineyards have recently introduced this new system on a small scale, whilst growers in England are increasingly relying on heating cables for frost protection.

ALTERNATIVES

For those looking for more low-tech, and potentially less expensive, solutions, alternative approaches including adapting one’s pruning regime. Delaying winter pruning – when the wood that won’t be needed next year is trimmed back – can have the effect of pushing back the date at which vines first produce buds in the spring. Delaying budbreak by a fortnight in the past was often sufficient, and meant the threat of the worst frosts had passed by the time the vines started to bud out. Sadly, as frosts happen later and later, with budbreak occurring ever earlier, this is less effective, and only means the green shoots will still be extremely delicate when frost does hit.

Other approaches include careful site selection, ensuring vineyards are planted on slopes, so that cold air drains away from the vineyard rapidly on freezing nights. On relatively flat landscapes though, such approaches are not possible, leaving grape-growers with a handful of expensive solutions that are in no way guaranteed to work.

LOOKING AHEAD

It is often said that to make a small fortune from a vineyard, one must start with a large fortune. As weather patterns change rapidly, and vignerons deal with severe frosts every year, even this bleak outlook is starting to seem optimistic.

For those producers setting up new vineyards, or looking to future-proof current vineyards, serious consideration needs to be given to built-in frost protection. Some producers may also prefer to select their grape varieties with this threat in mind, choosing those which are less susceptible to frost damage. And some, sadly, will decide this, combined with increasing droughts and heat spikes, is an insurmountable challenge. As further spring frosts bite, we will see more growers leave the wine industry altogether.