About this WINE

Jermann di Silvio Jermann SRL

Italy

After decades, centuries even, in the shadow of its neighbour France, Italy is finally getting the attention it deserves for its ancient and classic fine wines. It has always had the cards to play at the top table of fine wine – lofty sedimentary, calcareous and volcanic soils, noble autochthonous grapes bringing its individual terroir to life, a peerless gastronomic culture and a rich viticultural heritage – yet for centuries history has dealt it a tough hand.

It started well enough as the propagator of modern viticulture, first through the Etruscans and then the Romans who colonised their Empire with the help of the vine. With its breakup, and until Italy was re-united in 1861, the peninsula was divided by occupying forces, notably the Bourbons in the South, the Vatican in the Centre and the Austrians and French in the North. It had become the place where other European countries duelled to sort out their differences. Garibaldi and his Spedizione dei Mille (a volunteer corps of one thousand soldiers) cracked heads together during the First and Second Wars of Italian Independence, bringing the country together under Piedmont’s Savoia family, but the legacy of centuries of occupation had scarred the nation – not forgetting the damage wrought by the pest phylloxera during the late 19th century. It remained divided right through to the final ousting of the Austrians during the devastating Great War of 1915-1918, only to be set back by Mussolini’s Fascists, leading to mass emigration to South America, and the onslaught of another World War.

In 1946, the Republic was voted in by the slimmest of margins, but deep political differences remained, starkly between Communist and Fascist factions. The country’s viticultural structure remained relatively parochial, part of a polycultural system – along with olive oil, grain and livestock – catering for a local market (ie those that understood dialect), and lacking the British market that provided a lifeline to France, and Bordeaux in particular. On the verge of poverty, it was quantity not quality that initially drove the new Republican winemakers, as epitomised by the now infamous straw-wrapped Chianti ‘Fiasco’ bottle.

Fast forward to the emergence of export markets from the 1970s onwards, stimulated by the recently-created Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita (DOCG) which motivated former grape growers to bottle for quality. The North and Centre of Italy initially benefitted from the proximity of the Swiss and German markets, while a new American market took a shine to so-called ‘Super Tuscan’ wines that exploded onto the scene during the mid-1970s. This was the time of the Red Brigade: a new generation revolting against conservative restraints.

The South has suffered from the stigma of being a bulk producer – as slow adopters of the bottle. With the advent of the wine media in the 1980s (ie Parker and Wine Spectator in the USA), a channel was effectively created to feed a rapidly-growing demand for fine wine that accompanied unprecedented wealth. The results were potent: revolutionary winemakers and their equally famous consultants took centre stage, each one vying to be more extreme so as to catch the eye of the now-influential journalists. In Piedmont, one of these so-called ‘Barolo Boys’ took a chainsaw to his father’s traditional botti grandi (large barrels), replacing them with smaller barriques and provocatively planting French varieties instead of the native Nebbiolo. This ignited a mainly American thirst for these sensationalist wines, leading one magazine to announce in the mid-1990s that Napa Valley had finally arrived in the Langhe. Yet with the bursting of the economic bubble in 2008, and the end of the Berlusconi reign, it seems that even the most radical producers have turned full-circle, returning to the traditional, conservative style of fine winemaking.

So after the gloom and then the glitter, now is a great time to be discovering the delights of Italian fine wine. The current crop of producers have learnt from the past; they’re much more involved in the vineyard to bring the fruit to perfect ripeness – ideally organic and without excess. There’s less reliance upon technology to correct sub-standard wine, and more self-confidence and attention paid to the qualities of one piece of land over another, with a greater onus on authenticity. Wood ageing is no longer seen simply as a mechanism to impress, but more of a way to gently exalt the quality of the fruit and terroir.

Global warming appears to have had its say in Italy since 1995, delivering good to excellent vintages in all but a handful – another factor building confidence – the flipside to the climate change being unruly levels of sugar and alcohol. Autochthonous grapes are back in fashion as international (ie French) grapes wither on the vine; fruit is therefore increasingly cleaner, healthier and better-balanced, allowing for a wider drinking window starting a few years after the harvest, and lasting for up to 20 years for the key wine styles below. This is a most welcome development; a far-cry from the dirty, tough wines of the immediate post-War years, and from the alcoholic fruit-bombs that characterised Berlusconi’s bunga bunga era.

In the North, the key fine-wine styles, alongside Dolcetto and Barbera, are those of Piedmont’s Barbaresco and Barolo, born of the noble Nebbiolo grape, that combine rose perfume with extraordinary ageing potential of up to 20 years and beyond; the smaller volcanic zones of Gattinara and Bramaterra in the Alto Piedmont should also be considered. The Veneto’s Valpolicella Superiore Ripasso and Amarone are revered for their rich yet suave dried-fruit decadence, especially from the Corvina and Rondinella fruit grown in the hilly Classico villages.

Tuscany, in Italy’s Centre, is now undergoing something of a revolution itself as it rediscovers the bead-like beauty of their red Sangiovese grape: either through the fuller bodied wines of Brunello di Montalcino, the more reserved yet high-browed Vino Nobile di Montepulciano or as the brilliantly chiselled Chianti Classico; all three styles are capable of ageing for up to 20 years at least; Montecucco is a new zone to watch out for as it challenges neighbouring Montalcino.

Across the Appenines on the eastern seaboard of Italy one comes across the white Verdicchio grape of the Marche, which when grow at altitude in the Matelica zone is capable of impressive, Chardonnay-esque bottle development. Further down the Adriatic coast, the Abruzzo region is an emerging fine wine trove, now serving up lithe whites from the Trebbiano d’Abruzzo grape, or there are the brooding, soot and bramble reds of the Montepulciano d’Abruzzo grape; both capable for 10-15 yrs cellaring. Just across the Abruzzo border lies landlocked Umbria, famous for salty Orvieto but more importantly for cellaring: the Châteauneuf-like red Sagrantino di Montefalco, The South of Italy is particularly famous for the black Aglianico grape; otherwise known as the ‘Nebbiolo of the South’ on account of its noble elegance, natural balance and prodigious potential once in bottle.

In the state of Basilicata, high up on the slopes of the volcanic Vulture mountain it transforms into Aglianico del Vulture wine, a full, broad, smoky wine with 10 yrs + ageing; while across the border in Campania, in the shadow of Mount Vesuvius, the presence of calcareous white soils overlain with ash gives added verve and sinew to Aglianico’s extraordinary Taurasi wine, whose quivering energy imbues it with even longer life.

In the state of Basilicata, high up on the slopes of the volcanic Monte Vulture it transforms into Aglianico del Vulture, a full, broad, smoky wine with at least 10 years’ ageing; while across the border in Campania, in the shadow of Mount Vesuvius, the presence of calcareous white soils overlain with ash gives added verve and sinew to Aglianico’s extraordinary Taurasi wine, whose quivering energy imbues it with even longer life.

Meanwhile, from the stilettoed heel of Italy, in Puglia, come the full, heady, sumptuous, forest-fruit Primitivos that bear a fleeting resemblance to California’s Zinfandel; while, finally, in Sicily, from another lava-flow vineyard (that of Mount Etna) you’ll find the Etna Rosso wines, a supremely complex, red-orange-fruited, spice and smoky thing born of the local Nerello Mascalese grape.

If it’s wine for investment you’re after, you need to head to the Bolgheri region of Tuscany, where French varieties Cabernet and Merlot are grown on the coast, producing those aforementioned Super Tuscans: wines made to a similar recipe to those on the Gironde, but with more sun and a distinctly Italian accent.

Chardonnay

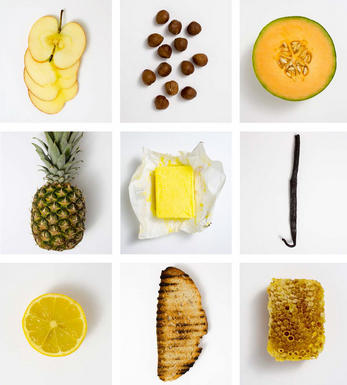

Chardonnay is often seen as the king of white wine grapes and one of the most widely planted in the world It is suited to a wide variety of soils, though it excels in soils with a high limestone content as found in Champagne, Chablis, and the Côte D`Or.

Burgundy is Chardonnay's spiritual home and the best White Burgundies are dry, rich, honeyed wines with marvellous poise, elegance and balance. They are unquestionably the finest dry white wines in the world. Chardonnay plays a crucial role in the Champagne blend, providing structure and finesse, and is the sole grape in Blanc de Blancs.

It is quantitatively important in California and Australia, is widely planted in Chile and South Africa, and is the second most widely planted grape in New Zealand. In warm climates Chardonnay has a tendency to develop very high sugar levels during the final stages of ripening and this can occur at the expense of acidity. Late picking is a common problem and can result in blowsy and flabby wines that lack structure and definition.

Recently in the New World, we have seen a move towards more elegant, better- balanced and less oak-driven Chardonnays, and this is to be welcomed.

Buying options

Add to wishlist

wine at a glance

Delivery and quality guarantee