About this SPIRIT

Dewazakura Sake Brewery

There are thousands of saké breweries in Japan and Dewasakura is located in Yamagata prefecture, and is one of the most prestigious. It was one of the first to seek to introduce a cool fermentation process with the aim of creating a delicate, refined product which could be drunk chilled. An effusive flowery bouquet is the unmistakable footprint of sakes from the Dewazakura Brewery in Yamagata Prefecture. Light, fragrant and delicious, the brewery’s ginjo labels are especially popular in Japan. Often called “winedrinkers’ sakes,” they do indeed possess fruity flavor notes reminiscent of certain white wines. They are totally free of any aftertaste and finish crisply and cleanly on the palate.

First, however, a bit of background. The brewing process for saké is very complex and takes much longer than for the production of beer or wine. The variety of rice used for saké, Sakamai, is not the same as that used for eating. It features larger, softer grains, and is more expensive, since it is only grown in certain areas and requires special cultivation techniques. 75% of all saké is made for commercial, mass-market use, and is produced by adding industrial alcohol and sugar to the fermenting rice. The result is undistinguished.

High-quality saké, however, is a labour of love, and the first requirement is to mill and polish the grains of rice to remove the fibre and protein, which form the outer husk. This leaves behind the central grain of starch, and as a rule the higher the percentage of the outer shell removed, the finer the resultant saké. Fermentation takes place slowly at 15°C or less, so often lasts months, but the low temperature is vital to maintain aroma and freshness.

The fermentation process requires the use of a microbe called Koji, similar to the agent which creates blue cheese, as this converts the starch in the rice grain to sugar. Yeast is added to convert the sugar into alcohol. In beer production this is a 2-stage process, but in the case of saké this happens simultaneously; it is called “multiple parallel fermentation”, and is a unique feature of saké production which distinguishes it from any other brewing process.

The quality of the water in which the rice grains are steeped prior to heating and subsequent fermentation is extremely important; semi-hard water is needed as it is low in iron and manganese, and this creates a more rounded quality in the finished product, free from harshness.

High-quality saké should be served chilled; saké served warm is generally made from lower-grade ingredients which the heating process is designed to disguise. Age is not highly valued in saké as freshness, fruitiness and smoothness are the qualities most revered.

There are three main categories of high-quality saké, named, in ascending order of quality, Junmai, Junmai-Ginjo and Junmai Daiginjo. The higher qualities are usually linked to the percentage of grain left after the polishing and milling process, with Junmai Daiginjo often being made from grains where a mere 30% of the original volume remains.

Saké is, of course, usually consumed with Japanese food, but I see no reason why it should not partner Western food perfectly well. In terms of texture, weight and acidity profile it seems to most closely resemble White Burgundy or White Hermitage, so I would recommend serving it between 12-15 degrees with fish dishes and white meats.

Rice

Alcoholic beverages made from rice, are based on the fermentation of rice starch which converts to natural sugars and alcohol. Unlike the production of beer which utilises mashing to convert starch to sugars, the rice beverage making relies on action of acids or enzymes like amylase.

Rice-based beverages typically have a higher alcohol content, 18%–25% abv, than still wine (9%–15%), and a higher alcohol content than the standard beers (usually 4%–6%).

Sake (a Japanese rice-based brewed alcohol) is misleadingly referred to as Rice Wine, although unlike wine, in which alcohol is produced by fermenting sugar that is naturally present in grapes, sake is produced by means of a brewing process more akin to beer.

Buying options

Add to wishlist

Description

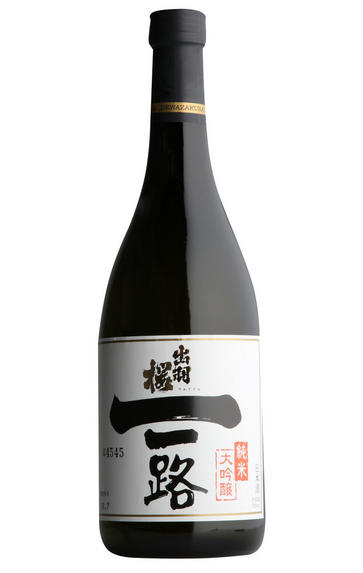

This top-scoring sake was the winner of the London International Wine Challenge 2008.

This has the delicate flowering-meadow aroma profile characteristic of a Daiginjo sake that has been crafted through a slow fermentation process of 26 days at a low temperature of 10ºC or less. After the addition of the Koji enzyme, a type of yeast called Ogawa is also added to the rice in order to complete its fermentation and to add a fruity spectrum of tropical flavours typical of this breed of Japanese yeast.

The rice for this Daiginjo has been polished to a grade where just 45% of the original grain was left, making it a light bodied sake with a rounded palate. Best enjoyed with light appetizers or by itself would be amazing too!

Alejandro Noda Vila, London Shop Advisor

spirit at a glance

Delivery and quality guarantee